MAX ERNST

Max Ernst (Brühl, April 2, 1891 – Paris, April 1, 1976) was a German-born French painter and sculptor, considered one of the most important artists of the twentieth century. A central figure of the European avant-garde, Max Ernst is remembered as a pioneer of Dada art and an absolute protagonist of surrealism, a movement he fervently adhered to, profoundly influencing his artistic production and worldview.

Max Ernst was born in Brühl, near Cologne, into a bourgeois family: his father, a teacher for the deaf and a amateur painter, played a fundamental role in his artistic education. After enrolling at the University of Bonn in 1909 to study philosophy and psychology, Ernst soon abandoned these studies to fully dedicate himself to art. In 1912, together with August Macke, he founded the group “Das Junge Rheinland,” exhibiting some of his early artworks in Cologne.

The experience of the First World War was crucial for Max Ernst: enlisted as a soldier, he experienced a trauma that would radically affect his view of reality and his artistic language. The absurdity of war pushed him to develop a fierce critique of Western culture and to seek new expressive forms capable of representing the irrational and the unconscious. As he wrote in his autobiography, Max Ernst symbolically died in 1914 and was reborn in 1918 as an artist determined to explore the fundamental myth of his era. This desire to break with traditional rationality led him first to Dadaism and then to surrealism.

His approach to surrealism occurred in the early 1920s, when he moved to Paris and met André Breton and Paul Éluard. The alliance with the surrealists was decisive for his career: Max Ernst and surrealism became an inseparable pair in modern art. Through the use of innovative techniques such as frottage (a practice involving rubbing a pencil on paper placed over an uneven surface) and grattage (removing upper layers of paint to create textures and unexpected images), Ernst explored the mechanisms of chance and the unconscious, key principles of surrealist poetics.

The surrealist period of Max Ernst was also characterized by intense work on collage: using fragments of illustrations, catalogs, and magazines, he created disturbing and hallucinatory images, often with a sharp irony that mocked bourgeois society’s values. An example is his collage-novel “La Femme 100 têtes” (1929), an emblematic work of visual surrealism, followed by “Une semaine de bonté” (1934), where Max Ernst’s surrealism merges into a new, dreamlike, and unsettling visual language.

Other works, such as the cycle “Histoire naturelle” (1926), show his deep interest in the psychology of the unconscious and the automatic mechanisms of artistic creation. The frottage technique became for Ernst the pictorial equivalent of surrealist automatic writing.

During the Second World War, Max Ernst, being German, was arrested by the French government and later persecuted by the Nazis. After various vicissitudes, he managed to escape to the United States with the help of patron Peggy Guggenheim, whom he married in 1942. In America, Ernst met Dorothea Tanning, whom he married in 1946 and with whom he shared an intense artistic and personal life.

During the American period, Ernst continued his innovative research, experimenting with new techniques such as oscillation, a precursor to dripping later made famous by Jackson Pollock. In Arizona, where he lived for several years, he created important sculptures and artworks marking a new phase of his career, while remaining anchored to surrealist poetics.

In 1953, Max Ernst returned to Europe, consolidating his international fame: in 1954 he won the first prize at the Venice Biennale, the highest recognition of his career and influence on contemporary art. Until his death in Paris in 1976, Ernst continued to work, experiment, and innovate, faithful to his rebellious spirit and the surrealist vocation he had embraced since the 1920s.

The bond between Max Ernst and surrealism remains central to the interpretation of his work: the irrational, the dream, the unconscious, and automatism always guided his research, making him one of the greatest interpreters of surrealist poetics, capable of merging technique and vision into new, surprising, and provocative forms.

Max Ernst artworks

Max Ernst’s artworks represent a perfect synthesis between technical invention and visionary imagination. From the beginning, his paintings, collages, and graphic production reveal a desire to break with traditional representation to explore the realms of the absurd and the dreamlike.

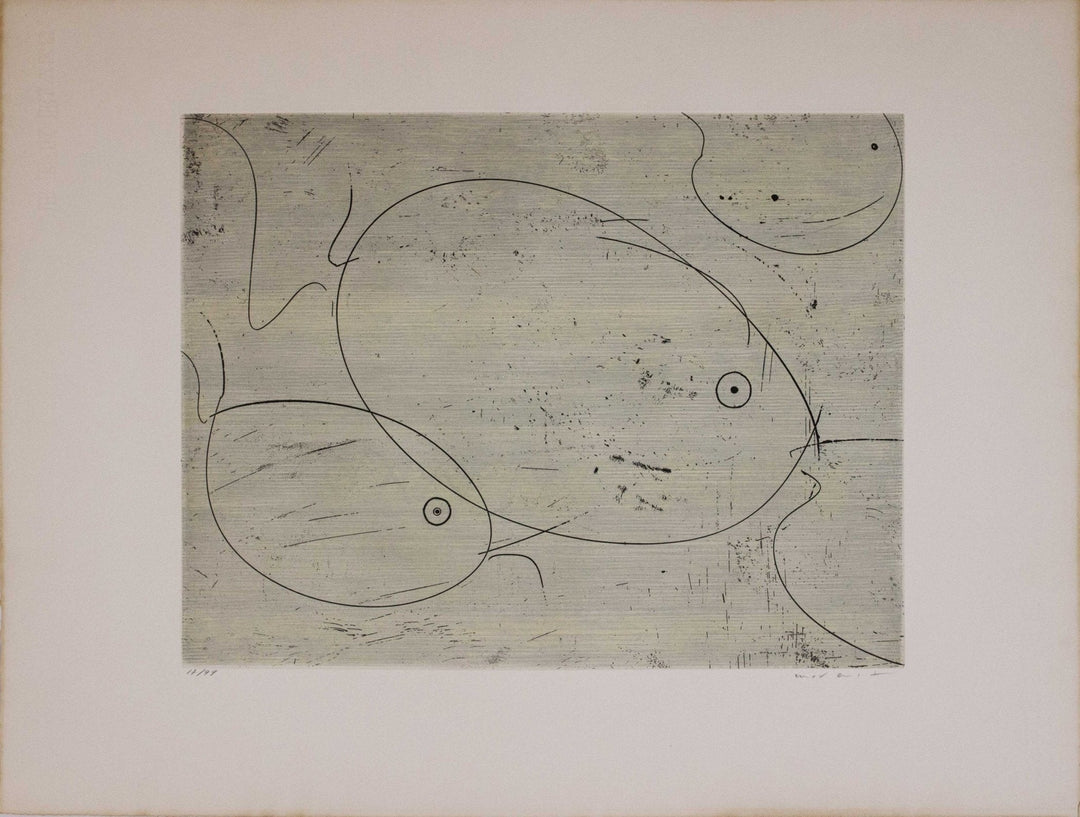

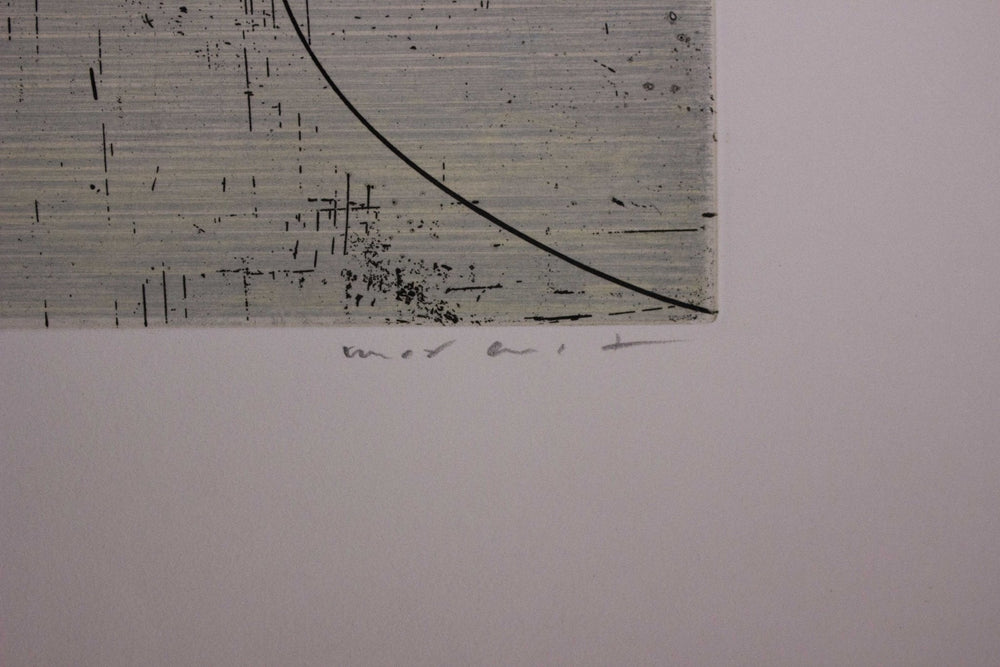

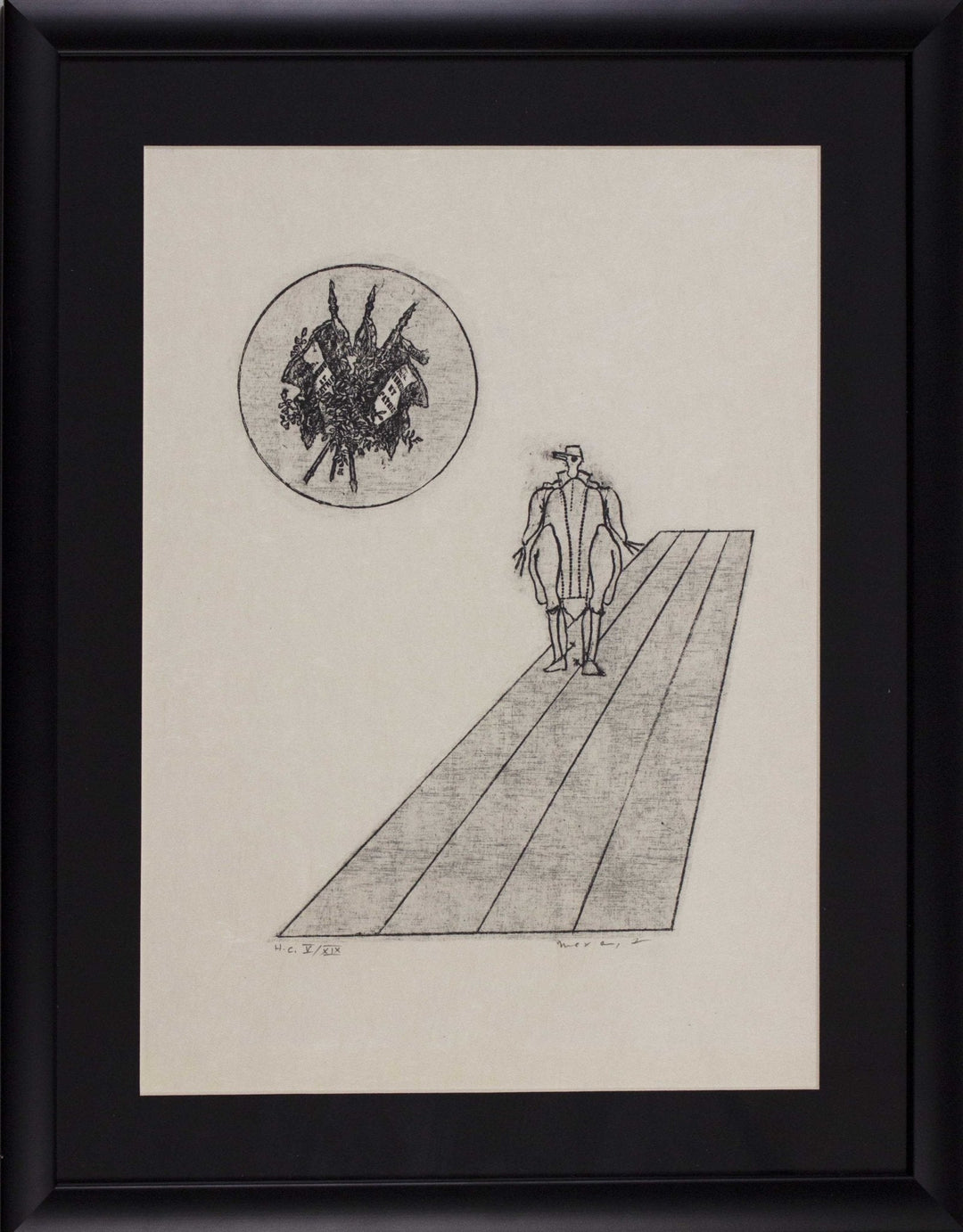

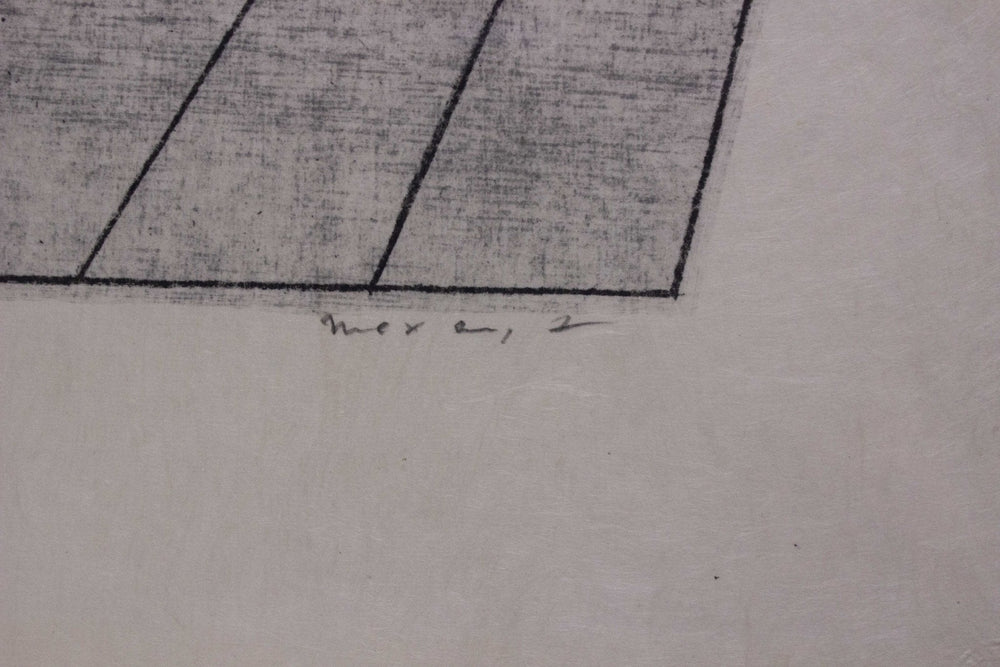

Alongside his famous paintings and collages, Max Ernst also devoted great intensity to graphics, producing numerous lithographs and etchings, often linked to his surrealist and hallucinatory themes. The lithograph album Fiat Modes Pereat Art, inspired by the discovery of De Chirico’s metaphysical art, testifies to Ernst’s attention to graphic experimentation already in the early years of his career.

Among the best-known pictorial masterpieces are “The Elephant Celebes” (1921), one of the first surrealist paintings, while “The Entire City” (1935/36) is another example of Max Ernst’s artworks created with the grattage technique, where fantastic architectures emerge from dense material surfaces.

Collage was also central to his production: “The Hat Makes the Man” (1920) is one of the most famous Dadaist collages; “Loplop Introduces Loplop” (1930) introduces the artist’s alter ego, the bird-man Loplop, a recurring figure in Max Ernst’s paintings and graphic artworks.

Graphic production reaches very high levels in collage-novels such as La Femme 100 têtes (1929) and Une semaine de bonté (1934), where Ernst creates surreal images through the combination and transformation of nineteenth-century engravings, scientific texts, and illustrated catalogs.

Equally significant are some surrealist etchings, in which the artist continues to experiment with unexpected material and visual effects, exploring the relationship between automatism and figurative form.

Finally, among the later Max Ernst artworks, sculptures such as “The King Playing with the Queen” (1944) stand out, demonstrating the coherence of his research, always aimed at technical innovation and overcoming the traditional boundaries of art.

In summary, the paintings, sculptures, lithographs and etchings constitute a fundamental corpus for understanding the renewal of twentieth-century art, demonstrating how surrealism was not just a style but a radical and free way of thinking and representing the world.